|

lento pede ambulabis

|

|

Le otto manifestazioni di Padmasambhava

Libera traduzione non autorizzata di

The Dance of the Guru's Eight

Aspects, Cathy Cantwell, The Tibet Journal Vol. 20, No. 4 (Winter 1995),

pp. 47-63 (17 pages) Published by: Library of Tibetan Works and

Archives

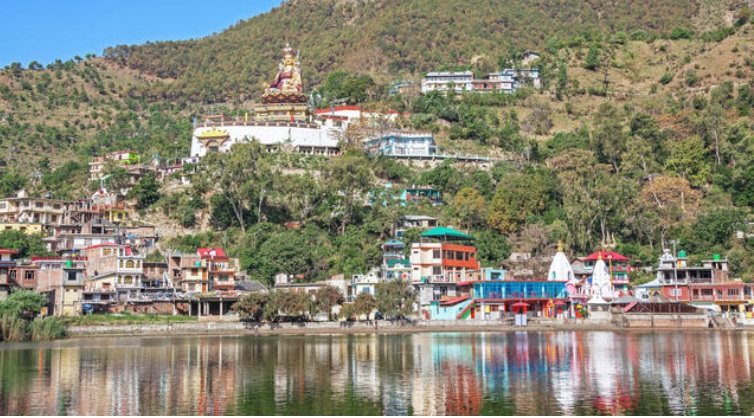

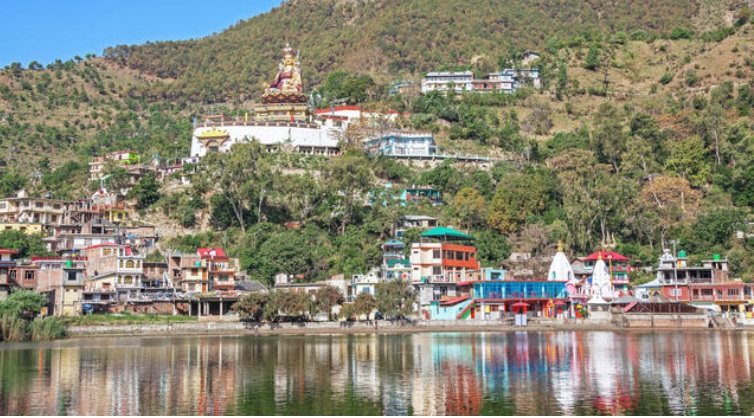

Vicino al sacro lago di

Rewalsar (tib: Tso Pema མཚོ་པད་མ།), meta di pellegrinaggio

buddhista, sorge l'omonimo convento della tradizione Drukpa Kagyupa

(riportato ance come ,

མཚོ་པདྨ་ཨོ་རྒྱན་ཧེ་རུ་ཀ་རྙིང་མ་པ་དགོན་པ།

Tso Pema Orgyen Heruka Nyingmapa Gompa considerando il lignaggio Drukpa come discendente dai Byigma.pa), la

stessa tradizione di Hemis e di alcuni monasteri dello Zanskar.

Cathy Cantwell ha assistito e descritto le danze 'cham

di Rewalsar che presentano aspetti simili ai 'cham del gonpa di

Hemis e che possiamo ritrovare anche nel Padum Hurim. Vicino al sacro lago di

Rewalsar (tib: Tso Pema མཚོ་པད་མ།), meta di pellegrinaggio

buddhista, sorge l'omonimo convento della tradizione Drukpa Kagyupa

(riportato ance come ,

མཚོ་པདྨ་ཨོ་རྒྱན་ཧེ་རུ་ཀ་རྙིང་མ་པ་དགོན་པ།

Tso Pema Orgyen Heruka Nyingmapa Gompa considerando il lignaggio Drukpa come discendente dai Byigma.pa), la

stessa tradizione di Hemis e di alcuni monasteri dello Zanskar.

Cathy Cantwell ha assistito e descritto le danze 'cham

di Rewalsar che presentano aspetti simili ai 'cham del gonpa di

Hemis e che possiamo ritrovare anche nel Padum Hurim.

Cantwell ha

numerose pubblicazioni sull'are come "Rewalsar: Tibetan Refugees in A

Buddhist Sacred Place", The Tibet Journal 20 1985,

Powerful Places and Spaces in Tibetan Religious Culture.

Oggi il lago è sorvegliato dalla ciclopica statua di Guru Rinpoche.

DANCE OF THE GURU'S

EIGHT ASPECTS

The "ground" of the outer and the

mental environment into a Buddha-field, and so on.

Many 'chams,

such as the Phur-'chams of the Fifth Dalai Lama's text, are divided into two main sections: a "Root Dance" for the "Realisation

of Enlightenment", and a following section for "Liberating

Negativity". This corresponds to the two basic divisions of

Mahayoga yi-dam deity practice in general.

Each dancer or set of dancers normally

move in a clockwise circular path, sometimes marked by

concentric circles outlined with flour or chalk.

The style of dancing depends on the nature of the figures

portrayed, and the type of ritual activity they are performing.

Black Hat dancers, Buddhas, yi-dams and high-ranking dharmapalas,

often dance with slow dignified movements. Every movement has a

significance; much of the Fifth Dalai Lama's obstacles to

realisation, may retain their "untamed" appearance, and perform

running and stamping "dances".

|

|

DANZA DEGLI OTTO ASPETTI DEL GURU

La "base" dell'ambiente esteriore e

mentale in un campo di Buddha, e così via.

Molti 'cham, come i

Phur-'cham (menzionato ndt) nell testo del

Quinto Dalai Lama, sono

divisi in due sezioni principali: una "Danza Radice" per

la "Realizzazione dell'Illuminazione" e una sezione

successiva per "Liberare la Negatività".

Ciò corrisponde alle due divisioni fondamentali della

pratica delle divinità

yi-dam del Mahayoga in generale

(contrazione del tibetano:

yid-kyi-dam-tshig, Impegno della Mente e Yi-dam Mente Sacra).

Ogni danzatore o gruppo di danzatori si

muove normalmente seguendo un percorso circolare in senso

orario, a volte segnato da cerchi concentrici delineati con

farina o gesso. Lo stile della danza

dipende dalla natura delle figure ritratte e dal tipo di

attività rituale che stanno svolgendo. I danzatori del Cappello

Nero, i Buddha, gli yi-dam e i dharmapala di alto rango,

spesso

danzano con movimenti lenti e dignitosi. Ogni movimento ha un

significato. Molti degli ostacoli alla

realizzazione del Quinto Dalai Lama possono mantenere il loro

aspetto "selvaggio" ed eseguire "danze" di corsa e scalpitando.

|

|

The Black Hat dancers and the chief

deities usually wear their costumes over their monastic robes.

Their costumes are mostly made of brocade and silk, sometimes

with elaborate embroideries, and they are adorned in accordance

with the particular deity's iconographical attributes. The mask

depicting the deity's face may be made of layers of cloth, glued

together around a clay model which is broken when the glue is

dry, or of papier-mâché, or carved wood. They may be two or

three times head size; the dancer sees through the nostrils or

mouth. Lesser deities generally wear less elaborate costumes.

|

|

I danzatori del Cappello Nero e le

divinità principali di solito indossano i loro costumi sopra le

vesti monastiche. I loro costumi sono per lo più realizzati in

broccato e seta, a volte con ricami elaborati, e sono adornati

in base agli attributi iconografici della divinità specifica. La

maschera che raffigura il volto della divinità può essere

composta da strati di stoffa, incollati insieme attorno a un

modello in argilla che si rompe quando la colla è asciutta,

oppure di cartapesta o di legno intagliato. Possono essere due o

tre volte più grandi della testa; il danzatore vede attraverso

le narici o la bocca.

Le divinità minori generalmente indossano

costumi meno elaborati.

|

THE GURU MTSHAN BRGYAD 'CHAMS

|

|

IL GURU MTSHAN BRGYAD 'CHAM |

According to my informants in Rewalsar,

the Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams - Dance of the Guru's Eight

Aspects - was introduced by the great rNying-ma-pa gter-ston,

Guru Chos-kyi dBang-phyug (1212-70) or Guru Chos-dbang for

short. In meditation, he visited Zangs mdog dpal ri (The

Glorious Copper-coloured Mountain), the Buddha-field of Guru

Padma, and he observed the

dākas,

dākinīs, and various forms

of the Guru, dancing. When he "returned" to the ordinary level

of experience, he taught the dances, which became very popular

in Tibet; they were performed in many rNying-ma-pa monasteries,

and also in some bKa'-rgyud-pa monasteries.

Based on Guru Chos-dbang's teaching, the

order and the steps of the dances of the Guru's áspects are the

same in each case, and although there are slight variations in

the decorations of the costumes, each aspect has his

characteristic features and is clearly recognisable. There is no

daaborate costumes.

|

|

Secondo i miei informatori a Rewalsar, il

Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams - Danza degli Otto Aspetti del Guru

- fu introdotto dal grande

rNying-ma-pa gter-ston, Guru Chos-kyi dBang-phyug

(tib. གུ་རུ་ཆོས་ཀྱི་དབང་ཕྱུག་) (1212-70) o

in breve

Guru Chos-dbang.

In meditazione, egli

visitò

Zangs mdog dpal

ri (La Gloriosa Montagna Color Rame), la

residenza di

Guru Padma, e osservò

danzare

i dāka, le dākinī

e varie forme del Guru.

Quando "tornò" al livello ordinario di esperienza, insegnò le

danze, che divennero molto popolari in Tibet e

vennero

eseguite in molti monasteri rNying-ma-pa e anche in alcuni

monasteri bKa'-rgyud-pa.

Basandosi sull'insegnamento di Guru Chos-dbang, l'ordine e i

passi delle danze degli aspetti del Guru sono gli stessi in ogni

caso e, sebbene vi siano lievi variazioni nelle decorazioni dei

costumi, ogni aspetto ha i suoi tratti caratteristici ed è

chiaramente riconoscibile.

Non ci sono costumi elaborati.

|

THE GURU MTSHAN BRGYAD 'CHAM

There is no dance manual associated with

the dance, but the tradition is orally preserved. The Guru

always "manifests" in this dance on the tenth day of the moon,

the time when, according to the "myth", Guru Padma promised to

return and to be present in person. In the Vajrayana, the tenth

day is considered to display the energy of the male heruka; Guru

Padma can be seen as the enlightened heruka par excellence, and

throughout the year, Guru Padma Tshogs offerings are performed

on the tenth day.

Nonetheless, Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams are

not always identical in that there may be variations in the

dances of the retinue, some involving more dances than others,

and while some, like the 'chams at Rewalsar, focus on the Guru's

appearance, at other monasteries the Eight Aspects dance is

integrated into another 'chams. For example, at a 'chams

observed by G.A. Combe (1926: Ch.XV, 179-198) at Tachienlu, the

"manifestation" was followed on the eleventh day by a

'chams of

rDo-rie Phur-pa, which culminated in a "Casting the gtor-ma" (gtor-rgyab)

ritual. Similarly, in the Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams at the '

Brug-pa monastery in Tashi Jong, an elaborate Phur- chams was

performed on the ninth day, and there were further dances of

wrathful emanations in the mandala of Guru Padma on the eleventh

day. According to Nebesky-Wojkowitz (1976: 38-40), there are two

alternative sequences in the Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams in the '

Brug-pa monastery at Hemis, Ladakh: either there are additional

dances of homage to the Guru, or there is a second day and a

number of dances demonstrating the destruction of negativity

embodied, in a liñga, followed by a dedication of animals in a

"scapegoat" type ritual.

|

|

IL GURU MTSHAN BRGYAD 'CHAM

Non esiste un manuale di danza associato a

questa danza, ma la tradizione è tramandata oralmente. Il Guru

si "manifesta" sempre in questa danza il decimo giorno della

luna, il momento in cui, secondo il "mito", Guru Padma

promise di tornare e di essere presente di persona.

Nel Vajrayana, il decimo giorno è considerato la manifestazione

dell'energia dell'heruka maschile; Guru Padma può essere

visto come l'heruka illuminato per eccellenza e, durante

tutto l'anno, le offerte a Guru Padma Tshog vengono

eseguite il decimo giorno. Tuttavia, i 'cham del Guru mTshan

brgyad non sono sempre identici, in quanto possono esserci

variazioni nelle danze del seguito, alcune delle quali prevedono

più danze di altre, e mentre alcune, come i 'cham di Rewalsar,

si concentrano sull'apparizione del Guru, in altri monasteri la

danza degli Otto Aspetti è integrata in un altro 'cham.

Ad

esempio, in un 'cham osservato da G.A. Combe a Tachienlu, la "manifestazione" era seguita

l'undicesimo giorno da un 'cham di rDo-rie Phur-pa, che

culminava nel rituale del "Lancio del gtor-ma" (gtor-rgyab).

Allo stesso modo, nel Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams presso il

monastero 'Brug-pa di Tashi Jong, il nono giorno veniva eseguito

un elaborato Phur-chams, e l'undicesimo giorno si svolgevano

ulteriori danze di emanazioni irate nel mandala di Guru Padma.

Secondo Nebesky-Wojkowitz (1976: 38-40), nel Guru mTshan brgyad

'chams del monastero 'Brug-pa di Hemis, in Ladakh,

si possono osservare due sequenze alternative: o danze

aggiuntive di omaggio al Guru, oppure un secondo giorno con una

serie di danze che dimostrano la distruzione della negatività

incarnata in una liñga, seguita dalla dedicazione

di animali in un rituale di tipo "capro espiatorio"

(come abbiamo visto a Stongde nell'inverno 1993 ndt).

Torna all'inizio |

|

From the available accounts, it seems that the basic structure

of the Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams itself involves three sections.

First, there are dances to prepare the ground and transform it

into the Buddha-field.

Usually, these consist of dances of the "ten wrathful ones" (khro-bo

bcu) or of Vajra Masters wearing the Black Hat costume. |

|

Dai resoconti disponibili, sembra che la

struttura di base del Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams stesso comprenda

tre sezioni. Innanzitutto, ci sono le danze per preparare il

terreno e trasformarlo nel campo di Buddha.

Di solito, queste consistono in danze dei

"dieci irati" (khro-bo bcu) o dei Maestri Vajra

che indossano il costume del Cappello Nero. |

|

Second, there are dances of the dÄkas and

dÄkinÄ«s of Guru Padma's retinue. Although based on

Guru Chos-dbang's visions, there is some variation here, some

monasteries performing elaborate dances of different groups in

the retinue, while others simply have one set.

Third, there are dances of the eight aspects. Other figures from

the "mythical" historical accounts of the establishment of the

early teaching lineages in Tibet, such as the King Khri-Srong

Ide-brtsan, the Mahayana scholar Å Äntaraksita, and the Vajra

Master Vairocana, may also appear. Once the eight aspects are

present, but before they dance, various figures enter to pay

homage to the Guru, and after the Guru's dances, there may be

further dances of offerings and praises.

|

|

In secondo luogo, ci sono le

danze dei dāka

e delle dākinī

del seguito di Guru Padma.

Sebbene basate sulle visioni

di Guru Chos-dbang,

presentano alcune varianti:

alcuni monasteri eseguono

elaborate danze di diversi

gruppi del seguito, mentre

altri ne hanno semplicemente

una.

In terzo luogo, ci sono le

danze degli otto aspetti.

Possono comparire anche

altre figure tratte dai

resoconti storici "mitici"

della fondazione dei primi

lignaggi di insegnamento in

Tibet, come il re

Khri-Srong Ide-brtsan,

lo studioso Mahayana

āntaraksita e il Maestro

Vajra Vairocana.

Una volta

che gli otto aspetti sono

presenti, ma prima di

danzare, varie figure

entrano per rendere omaggio

al Guru e, dopo le danze del

Guru, possono esserci

ulteriori danze di offerte e

lodi.

Torna all'inizio

|

|

|

|

THE GURU MTSHAN BRGYAD 'CHAMS AT

REWALSAR

PREPARATIONS

The annual performance of the Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams at

Rewalsar dates from a visit by sTag-lung-rtse sprul Rin-po-che

on bDud-'joms Rin-po-che's request, for the purpose of

instructing the monks. In 1982, only two of the monks actually

dancing (not including the musicians) had received teaching at

this time, but each year, practices were organised, and monks

who had not previously danced could learn. The then caretaker

monk, who was one of the original practitioners and clearly a

talented dancer, began a practice group during the twelfth

Tibetan month.

The group of six practised in the courtyard for about one hour

every evening, with the caretaker monk demonstrating the steps

of the Zhva-nag (Black Hat) dances, and in a good-humoured way,

imitating clumsiness to show how not to dance. Three had never

previously participated in a 'chams, and the oldest of these

eventually dropped out and joined the monks providing the

musical accompaniment on the tenth day.

There was, in fact, a

shortage of monks, since a few were in the monastery's retreat,

and when the senior dbu-mdzad ("Head monk", or "Master of

Ceremonies" in the context of much monastic ritual) was

prevented by backtrouble from providing further coaching, there was some

uncertainty as to whether there would be a 'chams at all. The

practices were interrupted for two days, but when the slob-dpon

(the "Vajra Master", in charge of the monastery's ritual

practice) returned from his visit to Nepal, he decided that the

'chams should go ahead, even if some of Guru Padma's aspects

might not be able to dance; and he asked one of the monks in

retreat to come out for the practice session (which began a week

before the 'chams), to provide the final instruction.

The practices resumed, sometimes presided over by the slob-dpon

who timed the steps by playing the cymbals. The dancers included

two Young monks from the 'Bri-gung bKa'-rgyud-pa monastery, and

a monk from a rNying-ma-pa monastery in Kinnaur, who had learnt

and participated in the 'Ähams at Rewalsar three years

previously. When the monk came out of retreat to coach the

dancers, he taught the group the Ging 'chams, and through the

process of his teaching the various dances of the eight

aspectsand discussion with the slob-dpon, the roles of the

different aspects were gradually allocated. The senior dbu-mdzad

recovered enough to join the final rehearsal and to perform the

Black Hat dance and the dance of Padmasambhava; monks from the

bKa'-rgyud-pa monastery wore the costumes of the two consorts of

Guru Padma and the two aspects, Åakya Seng-ge and Blo-ldan

mChog-sred, who did not dance.

A

few days before the 'chams, two of the monks checked the

costumes which are stored in the upper storey of the temple, and

made the necessary repairs.

The final rehearsal, complete with the textual and musical

accompaniment, but without the costumes, took place on the

evening of the ninth day. The monk musicians were mainly older

monks who had danced in previous years.

|

|

IL GURU MTSHAN BRGYAD 'CHAMS

A REWALSAR

PREPARATIVI

L'annuale esibizione del

Guru mTshan brgyad 'cham

a Rewalsar risale a una

visita di sTag-lung-rtse

sprul Rin-po-che, su

richiesta di bDud-'joms

Rin-po-che, allo scopo

di istruire i monaci. Nel

1982, solo due dei monaci

che effettivamente danzavano

(esclusi i musicisti)

avevano ricevuto

insegnamenti in quel

periodo, ma ogni anno

venivano organizzate delle

pratiche e i monaci che non

avevano mai danzato in

precedenza potevano

imparare. L'allora monaco

custode, che era uno dei

praticanti originari e

chiaramente un ballerino di

talento, iniziò un gruppo di

pratica durante il

dodicesimo mese tibetano.

Il

gruppo di sei si esercitava

nel cortile per circa un'ora

ogni sera, con il monaco

custode che dimostrava i

passi delle danze

Zhva-nag (Cappello Nero)

e, in modo bonario, imitava

la goffaggine per mostrare

come non ballare. Tre di

loro non avevano mai

partecipato a un 'cham, e il

più anziano alla fine

abbandonò il gruppo e si unì

ai monaci per fornire

l'accompagnamento musicale

il decimo giorno. C'era,

infatti, una carenza di

monaci, poiché alcuni si

trovavano nel ritiro del

monastero, e quando il

dbu-mdzad anziano

("Capo Monaco", o "Maestro

di Cerimonie" nel

contesto di gran parte dei

rituali monastici) fu

impedito da problemi alla

schiena di fornire ulteriore

insegnamento, ci fu una

certa incertezza

sull'effettiva possibilità

di organizzare un 'cham. Le

pratiche furono interrotte

per due giorni, ma quando lo

slob-dpon (il

"Maestro del Vajra",

responsabile della pratica

rituale del monastero) tornò

dalla sua visita in Nepal,

decise che i 'cham dovessero

continuare, anche se alcuni

aspetti di Guru Padma non

fossero in grado di danzare;

e chiese a uno dei monaci in

ritiro di partecipare alla

sessione di pratica (che

iniziava una settimana prima

dei 'cham), per fornire le

istruzioni finali.

Le pratiche ripresero, a

volte presiedute dallo

slob-dpon che scandiva i

passi suonando i cimbali.

Tra i danzatori c'erano due

giovani monaci del monastero

'Bri-gung bKa'-rgyud-pa

e un monaco di un monastero

rNying-ma-pa nel Kinnaur,

che aveva imparato e

partecipato ai 'čham a

Rewalsar tre anni prima.

Quando il monaco uscì dal

ritiro per allenare i

danzatori, insegnò al gruppo

il Ging 'cham e, attraverso

l'insegnamento delle varie

danze degli otto aspetti e

la discussione con lo

slob-dpon, i ruoli dei

diversi aspetti furono

gradualmente assegnati. Il

dbu-mdzad anziano si riprese

abbastanza da poter

partecipare alla prova

finale ed eseguire la danza

del Cappello Nero e la danza

di Padmasambhava; i monaci

del monastero

bKa'-rgyud-pa

indossarono i costumi delle

due consorti di Guru Padma e

dei due aspetti, akya

Seng-ge e Blo-ldan

mChog-sred, che non

danzarono. Le pratiche ripresero, a

volte presiedute dallo

slob-dpon che scandiva i

passi suonando i cimbali.

Tra i danzatori c'erano due

giovani monaci del monastero

'Bri-gung bKa'-rgyud-pa

e un monaco di un monastero

rNying-ma-pa nel Kinnaur,

che aveva imparato e

partecipato ai 'čham a

Rewalsar tre anni prima.

Quando il monaco uscì dal

ritiro per allenare i

danzatori, insegnò al gruppo

il Ging 'cham e, attraverso

l'insegnamento delle varie

danze degli otto aspetti e

la discussione con lo

slob-dpon, i ruoli dei

diversi aspetti furono

gradualmente assegnati. Il

dbu-mdzad anziano si riprese

abbastanza da poter

partecipare alla prova

finale ed eseguire la danza

del Cappello Nero e la danza

di Padmasambhava; i monaci

del monastero

bKa'-rgyud-pa

indossarono i costumi delle

due consorti di Guru Padma e

dei due aspetti, akya

Seng-ge e Blo-ldan

mChog-sred, che non

danzarono.

Pochi giorni prima del 'cham,

due monaci controllarono i

costumi conservati al piano

superiore del tempio ed

effettuarono le riparazioni

necessarie.

La prova finale, completa di

accompagnamento testuale e

musicale, ma senza i

costumi, ebbe luogo la sera

del nono giorno. I monaci

musicisti erano

principalmente monaci

anziani che avevano danzato

negli anni precedenti.

Torna all'inizio

|

THE TENTH DAY 'CHAMS

The morning recitation practice began in the temple at 3.30 am.,

consisting of the full Bla-sgrub Las-byang ritual practice of

Guru Padma, which had already been practised intensively for

several days. The whole practice, including the Tshogs feast

offering (normally performed in the afternoon) was completed by

about 8.15 am., at which time the monks had a break. |

|

IL DECIMO GIORNO DI 'CHAM

La pratica della recitazione

mattutina iniziò nel tempio

alle 3:30, consistente

nell'intera pratica rituale

del Bla-sgrub Las-byang di

Guru Padma, che era già

stata praticata intensamente

per diversi giorni. L'intera

pratica, inclusa l'offerta

della festa di Tshogs

(normalmente eseguita nel

pomeriggio), fu completata

intorno alle 8:15, ora in

cui i monaci fecero una

pausa.

|

|

The scheduled start to the 'chams (9 am.) was postponed due to

heavy rain, and there was a further mantra recitation session in

the temple.

Meanwhile, spectators began to gather around the courtyard: most

of the audience were Buddhist hill people and Tibetan refugees,

with a few local Indians and westerners. At about 11 am., the

dancers began to don their costumes, and a couple of monks with

lay helpers prepared the dance arena. Meanwhile, two "jokers" (a-tsa-ra)

entertained the audience, and the monastery's visiting mkhan-po

(in charge of academic studies), the slob-dpon and the monk

musicians took their places along one side of the courtyard. |

|

L'inizio previsto del 'cham

(alle 9:00) fu posticipato a

causa della forte pioggia, e

ci fu un'ulteriore sessione

di recitazione dei mantra

nel tempio.

Nel frattempo, gli

spettatori iniziarono a

radunarsi intorno al

cortile: la maggior parte

del pubblico era composta da

buddhisti delle colline e

rifugiati tibetani, con

alcuni indiani locali e

occidentali. Verso le 11:00,

i danzatori iniziarono a

indossare i loro costumi e

un paio di monaci con

aiutanti laici allestirono

l'arena per le danze. Nel

frattempo, due "burloni" (a-tsa-ra)

intrattenevano il pubblico,

mentre il mkhan-po

(responsabile degli studi

accademici) in visita al

monastero, il "slob-dpon" e

i monaci musicisti

prendevano posto lungo un

lato del cortile.

Torna all'inizio |

THE ZHVA-NAG (BLACK HAT) AND GING

'CHAMS

A

procession of bKa'-rgyud-pa monks playing instruments led the

nine Zhva-nag (Black Hat) dancers into the courtyard, to the

accompaniment of the rNying-ma-pa monk musicians. I have dealt

with the Black Hat 'chams elsewhere; here, it suffices to note

that the four Zhva-nag dances prepare for the manifestation of

the Guru's aspects, by both purifying the outer and the inner

mental environment, and inviting the Guru's presence. The first

two dances demonstrate the ritual activities of "pacifying" and

"destroying", and the third gSer-skyems -"Golden drink" offering

- dance invites the deities of Guru Padma's mandala, along with

the dharmapãlas, to prepare the place for the arising of the

Guru, conferring their powers upon the practitioners. Finally,

there is a dance of return to the temple.

After the Zhva-nag dances, there was a break while the dancers

changed their costumes; eight of them were also to dance as Ging;

members of Guru Padma's retinue who announce his imminent

arrival.

The Ging 'chams is usually performed with eight dancers at

Rewalsar owing to the lack of monks - I was informed that

sixteen would by the ideal number. Half of the group are dpa'

-bo - "Heroes" or vīra (Skt.) and half are dpa' -mo - 'Heroines"

(vÄ«rÄ), the males wearing mock tiger skins and the females

wearing mock leopard skins. One informant said that rather than

representing the male/female division, the two types of Ging

were the Nam-ging ("Ging of the skies") and the Sa-ging (Ging of

the earth).

This division was also used in the Ging 'chams performed at the

'Brug-pa monastery in Hemis, Ladakh: see Nebesky-Wojkowitz.

|

|

LO ZHVA-NAG (CAPPELLO NERO)

E IL GING 'CHAM

Una

processione di monaci

bKa'-rgyud-pa

che suonavano strumenti

guidò i nove danzatori

Zhva-nag (Cappello Nero)

nel cortile, accompagnati

dai monaci musicisti

rNying-ma-pa. Ho già parlato

altrove dei 'cham del

Cappello Nero; qui, è

sufficiente notare che le

quattro danze Zhva-nag

preparano alla

manifestazione degli aspetti

del Guru, purificando

sia l'ambiente mentale

esterno che quello interno,

e invitando la presenza del

Guru. Le prime due danze

dimostrano le attività

rituali di "pacificazione"

e "distruzione",

e la terza danza

gSer-skyems -

l'offerta della "bevanda

dorata" - invita le

divinità del mandala di Guru

Padma, insieme ai dharmapãla,

a preparare il luogo per

l'apparizione del Guru,

conferendo i loro poteri ai

praticanti. Infine, c'è una

danza di ritorno al

tempio. Dopo le danze

Zhva-nag, ci fu una pausa

per il cambio d'abito dei

danzatori; otto di loro

avrebbero danzato anche come

Ging, membri del seguito di

Guru Padma che annunciano il

suo imminente arrivo.

Il

Ging'cham viene

solitamente eseguito con

otto danzatori a Rewalsar, a

causa della mancanza di

monaci; mi è stato detto che

sedici sarebbero

stati il numero ideale. Metà

del gruppo è composto da

dpa'-bo - "Eroi"

o vīra

(sanscrito) e metà da dpa'-mo

- "Eroine" (vīrā),

con i maschi che indossano

finte pelli di tigre e le

femmine che indossano finte

pelli di leopardo. Un

informatore ha affermato

che, anziché rappresentare

la divisione

maschile/femminile, i due

tipi di Ging erano il

Nam-ging ("Ging dei

cieli") e il

Sa-ging (Ging della

terra).

Questa

divisione era utilizzata

anche nei Ging 'cham

eseguiti presso il monastero

di

'Brug-pa a Hemis,

Ladakh (vedi Nebesky-Wojkowitz).

|

|

These two categories are not mentioned in the Bla-sgrub

Las-byang text where, in The Invitation, they are simply

referred to as the "Four Ging who subdue MÄra", and they are

situated in the four directions. Whether the twofold division is

on the grounds of gender or spatial location, the most important

classification of the Ging is according to their positions in

the mandala: two, one from each group, come from each of the

directions. This is expressed in the 'chams through the colours

of the masks: two are blue (east), two are yellow (south), two

red (west), and two green (north). The role of the Ging in the 'chams,

as those who "subdue MÄra", is to destroy clear away any

obstacles,26 so that the environment will be prepared for and

the observers receptive to the true

nature of the manifestation of the Guru, when they arise. As

members of Guru Padma's retinue, they are an expression of his

enlightened activities.

|

|

Queste

due categorie non sono

menzionate nel testo di

Bla-sgrub Las-byang,

dove, nell'Invito,

sono semplicemente chiamate

"Quattro Ging che

sottomettono Māra" e

sono situate nelle quattro

direzioni. Che la duplice

divisione sia basata sul

genere o sulla posizione

spaziale, la classificazione

più importante dei Ging è

determinata dalla loro

posizione nel mandala: due,

uno per ogni gruppo,

provengono da ciascuna

direzione. Questo è espresso

nei 'cham attraverso i

colori delle maschere:

due sono blu (est),

due sono gialle (sud),

due rosse (ovest) e

due verdi (nord). Il

ruolo dei Ging nei 'cham, in

quanto "sottomettono Māra",

è quello di distruggere e

rimuovere qualsiasi

ostacolo, in modo che

l'ambiente sia preparato e

gli osservatori ricettivi

alla vera

natura della

manifestazione del Guru,

quando si manifestano. Come

membri del seguito di Guru

Padma, sono un'espressione

delle sue attività

illuminate.

Torna all'inizio

|

|

The Tibetans specifically refer to these Ging who appear in the

mandala and in the 'chams, as Ging-chen, literally, "Great. Ging",

distinguishing them from minor ging who are a group of worldly

deities.

The Gings' masks have wrathful expressions, and each has

multicoloured fan-like adornments on either side and a

triangular flag attached above, with a long headdress hanging

down the back, from the top of the mask. The Ging wear brocade

poncho-like upper garments, "tiger" and "leopard skin" wraps,

with ornamental strips of overlapping pieces of cloth hanging

from their waists. Each Ging carries a pole drum in the left

hand and a drumstick in the right.

The Ging 'chams began with the dancers rushing from the temple

in two groups, beating their drums and running in different

directions around the courtyard. This part of the "dance" is

called gsum-skor, "three circumambulations", since both groups

go around three times. The cymbals were played quickly and

continuously throughout the dance, being joined by the horns at

the beginning and at the end as the dancers returned to the

temple. The seated monks recited a short praise to the Ging as

the assembly of Heroes/Heroines surrounding Hayagrîva yab-yum (Bla - sgrub Lasbyang). Then the eastern and

southern Ging formed one row, facing the northern and western

Ging, and they all danced in these positions, whirling, hopping,

bending over and kneeling.

They changed places, continued dancing and then became one

circle, dancing around in first one and then the other

direction. This circling is called, dgu-skor, "nine

circumambulations", since nine revolutions must be made. Finally,

the dancers ran back into the temple in a single file . |

|

I

tibetani si riferiscono

specificamente a questi Ging

che appaiono nel mandala e

nei 'cham come

Ging-chen,

letteralmente "Grandi".

Ging",

distinguendoli dai ging

minori, che sono un gruppo

di divinità mondane.

Le

maschere dei Ging hanno

espressioni irate e ciascuna

presenta decorazioni

multicolori a forma di

ventaglio su entrambi i

lati e una bandiera

triangolare attaccata

sopra, con un lungo

copricapo che pende dalla

parte superiore della

maschera. I Ging indossano

vesti superiori in broccato

simili a poncho, mantelli di

"pelle di tigre" e "pelle di

leopardo", con strisce

ornamentali di pezzi di

stoffa sovrapposti che

pendono dalla vita. Ogni

Ging porta un tamburo

damaro nella

mano sinistra e una

bacchetta nella destra.

I Ging

'cham iniziavano con i

danzatori che uscivano di

corsa dal tempio in due

gruppi, battendo i loro

tamburi e correndo in

direzioni diverse intorno al

cortile. Questa parte della

"danza" è chiamata

gsum-skor, "tre

circumambulazioni",

poiché entrambi i gruppi

compiono tre giri. I cimbali

venivano suonati velocemente

e ininterrottamente durante

la danza, a cui si univano i

corni all'inizio e alla fine

mentre i danzatori tornavano

al tempio. I monaci seduti

recitavano una breve lode al

Ging, mentre l'assemblea di

Eroi/Eroine circondava

Hayagrîva yab-yum (Bla-sgrub

Lasbyang). Quindi il Ging orientale e quello

meridionale formavano

un'unica fila, di fronte al

Ging settentrionale e a

quello occidentale, e tutti

danzavano in queste

posizioni, volteggiando,

saltellando, chinandosi e

inginocchiandosi.

Si

scambiavano di posto,

continuavano a danzare e poi

formavano un unico cerchio,

danzando prima in una

direzione e poi nell'altra.

Questo giro è chiamato

dgu-skor, "nove

circumambulazioni", poiché

devono essere compiute nove

rotazioni. Infine, i

danzatori tornavano di corsa

al tempio in fila indiana.

Torna all'inizio |

|

|

|

THE EIGHT ASPECTS

DANCE

Following an hour and a half's break during which the dancers

could rest and eat, at about 3 pm., the procession to lead on

the Guru and his aspects began. An older monk who had taken part

in the morning dances led, carrying a white flag topped with

burning incense. Behind, four monks held up "victory banners" (rgyal-mtshan);

these are used in cerimonial processions to mark the coming of a

high lama. They were followed by monks playing long horns and

trumpets, while the monk musicians alongside joined in making

music. Many spectators put the palms of their hands together in

respect as the Guru's aspects emerge from the temple.

In

the middle of the file walked the central form of the Guru

flankedby his two consorts, with a monk holding a large

ceremonial parasol over his head. The monastery's slob-dpon had

requested a local respected sngags - pa to act as the Guru,

since it is vital that the central figure should be an advanced

meditation practitioner who can maintain awareness of himself as

the Guru, and he should be felt by observers to embody Guru

Padma's presence. In front of the Guru, Sakya Seng-ge, Padma

rGyal-po and Padma - sambhava walked in file, and behind, Padma

'Byung-gnas, Blo-ldan mChog-sred and Nyi-ma 'Od-zer. They did

one circumambulation of the courtyard while the two wrathful

aspects, rDo-rje Gro-lod and Seng-ge sGra-sgrogs, danced,

whirling around the courtyard. Then, they seated themselves

along one side of the courtyard, the two wrathful aspects

completing their dance and taking their places at the two ends

of the line. Usually, I was told, ÅÄntaraksita and Khri-Srong

IDe-brtsan would also appear, as the other main figures who made

the rNying-ma-pa lineages possible, but they were not

represented because of the shortage of monks. |

|

LE DANZE DEGLI OTTO ASPETTI

Dopo

un'ora e mezza di pausa

durante la quale i danzatori

potevano riposare e

mangiare, verso le 15:00,

iniziò la processione che

precedeva il Guru e i suoi

aspetti. Un monaco anziano

che aveva preso parte alle

danze mattutine guidava la

processione, portando una

bandiera bianca sormontata

da incenso ardente. Dietro,

quattro monaci reggevano

"stendardi della vittoria" (rgyal-mtshan);

questi vengono utilizzati

nelle processioni

cerimoniali per celebrare

l'arrivo di un lama di alto

rango. Erano seguiti da

monaci che suonavano corni e

trombe, mentre i monaci

musicisti si univano alla

musica. Molti spettatori

univano i palmi delle mani

in segno di rispetto mentre

gli aspetti del Guru

emergevano dal tempio.

Al

centro della fila camminava

la figura centrale del Guru

affiancata dalle sue due

consorti, con un monaco

che reggeva un grande

parasole cerimoniale

sopra la testa. Il monaco

del monastero aveva

richiesto che un rispettato

sngags-pa

(laico

praticante ndt)

locale fungesse da Guru,

poiché è fondamentale che la

figura centrale sia un

praticante di meditazione

avanzato in grado di

mantenere la consapevolezza

di sé come Guru, e che gli

osservatori lo percepiscano

come l'incarnazione della

presenza di Guru Padma.

Davanti al Guru, Sakya

Seng-ge, Padma

rGyal-po e

Padma-sambhava

camminavano in fila, e

dietro, Padma 'Byung-gnas,

Blo-ldan mChog-sred e

Nyi-ma 'Od-zer.

Fecero un giro del cortile

mentre i due aspetti irati,

rDo-rje Gro-lod e

Seng-ge sGra-sgrogs,

danzavano, volteggiando

intorno nel

cortile. Poi, si sedettero

lungo un lato del cortile, i

due aspetti irati

completarono la loro danza e

presero posto alle due

estremità della fila. Di

solito, mi è stato detto,

apparivano anche

āntaraksita e

Khri-Srong Ide-brtsan,

le altre figure principali

che resero possibile la

stirpe rNying-ma-pa, ma

non erano

rappresentati a causa della

carenza di monaci.

|

|

Then, two more figures walked from the temple up to the central

form of the Guru to pay their respects. They were lndra and

Brahma, the great Hindu deities, who in Buddhist thinking,

became the kings of the worldly gods and peaceful protectors of

the Dharma. On behalf of all the forces of Samsara, which they

govern, they paid homage to the Guru.

To

the accompaniment of the cymbals and drums, the monk musicians

then began to chant praises to the Guru. The first three verses

from the Bla-sgrub Las-byang section of "Praises" praise the

Guru as the embodiment of the Trikaya, with the form of Samantabhadra, unobstructed speech and inconceivable unmoving

mind; his form arisen for the benefit of beings, ornamented with

Buddha marks and qualities, with complete mastery over the

phenomenal world. This section was followed with a verse praising the five

Thod-phreng-rtsals "Emanations

Garlanded with Skulls"- which encircle Guru Padma in the

Bla-sgrub Las-byang text, and beyond which the eight aspects

arise in the eight directions. The Thod-phreng-rtsals are

praised for their accomplishment of the four activities; with

the completion of this verse, the horns joined the cymbals in a

crescendo of music. |

|

Poi,

altre due figure si

diressero dal tempio verso

la figura centrale del Guru

per rendergli omaggio. Erano

Indra e Brahma, le

grandi divinità

hindu, che

nel pensiero buddhista

divennero i re degli dei

mondani e i pacifici

protettori del Dharma. A

nome di tutte le forze del

Samsara, da loro governate,

resero omaggio al Guru.

Accompagnati da cembali e

tamburi, i monaci musicisti

iniziarono quindi a cantare

lodi al Guru.

I primi tre

versi della sezione "Lodi"

del Bla-sgrub Las-byang

lodano il Guru come

incarnazione del Trikaya,

con la forma di

Samantabhadra,

(parola senza

ostacoli e mente

inconcepibilmente immobile)

la cui forma è sorta per il

beneficio degli esseri,

ornata dei segni e delle

qualità del Buddha, con

completa padronanza del

mondo fenomenico. Questa

sezione era seguita da un

verso che loda i cinque Thod-phreng-rtsal -

"Emanazioni inghirlandate di

teschi" - che circondano

Guru Padma nel testo del

Bla-sgrub Las-byang, e oltre

i quali gli otto aspetti

sorgono nelle otto

direzioni.

I Thod-phreng-rtsal sono

lodati per il loro

compimento delle quattro

attività; al termine di

questo verso, i corni si

unirono ai cimbali in un

crescendo musicale.

Torna all'inizio

|

The dance of Padma 'Byung-gnas began. With the cymbals playing,

this aspect, dressed in accordance with the iconography of the

form usually called " O-rgyan rDo-rje 'Chang', rose from his

seat, and performed a slow dance with some whirling around. In

his right hand, he held a rdo-rje and in his left, a bell; as he

danced, he crossed over and uncrossed his arms several times,

presumably demonstrating the inseparability of wisdom (the bell)

and means (the rdo-rje).

While he danced, the lines praising

Padma 'Byung-gnas were recited very slowly:

"Free from attachment, undefiled by any fault;

I praise the form of Padma ' Byung-gnas' "

The dance is called, "mTsho-kyi bzhad-pa'i stangs-stabs" , "Movement

of blossoming from the lake", and it is associated with the

"birth" of Padmã-kara from the lotus in the land of O-rgyan.

This aspect, then, demonstrates the origination of Guru Padma's

manifestation in the world and expresses his primordial Buddha

nature.

|

|

La

danza di Padma 'Byung-gnas

ebbe inizio. Al suono dei

cimbali, questo personaggio,

vestito secondo

l'iconografia della forma

solitamente chiamata "O-rgyan

rDo-rje 'Chang'", si alzò

dal suo posto ed eseguì una

danza lenta con alcuni

movimenti rotatori. Nella

mano destra teneva un

rdo-rje e nella sinistra una

campana; mentre danzava,

incrociò e sciolse le

braccia più volte,

presumibilmente a

dimostrazione

dell'inseparabilità tra

saggezza (la campana) e

mezzi (il rdo-rje).

Mentre

danzava, i versi in lode di Padma 'Byung-gnas venivano

recitati molto lentamente:

"Libero da attaccamento,

incontaminato da qualsiasi

colpa;

Lodo la forma di Padma 'Byung-gnas'"

La

danza è chiamata "mTsho-kyi

bzhad-pa'i stangs-stabs",

"Movimento della fioritura

dal lago", ed è

associata alla "nascita" di

Padmā-kara dal loto nella

terra di O-rgyan. Questo

aspetto, quindi, dimostra

l'origine della

manifestazione di Guru Padma

nel mondo ed esprime la sua

natura primordiale di

Buddha.

|

|

The dance of Padmasambhava followed. Wearing saffron robes and

the hat of an ācarya, he carried a skull-cup in his left hand,

and throughout the dance, his right hand was in the teaching

mudrÄ. This dance was also slow and graceful; he lifted one leg

straight out, turned, and then slowly moved his leg down, lifted

the other leg, and so on. The dance is called, "Yon-tan-gyi

rba-rlabs gYo-ba 'i stang-stabs" , "Movement of the rolling

waves of Buddha qualities", here implying the qualities of

knowledge and wisdom contained in his teachings, since

Padmasambhava is essentially the aspect of Guru Padma as the

Dharma teacher who established the monastery of bSam-yas and

thus, Buddhism in Tibet. With the cymbals stillplaying, the

monks recited his praise:

"The One who has fully perfected all Buddha qualities;

I praise the form of Padmasambhaval" |

|

Seguì

la

danza di Padmasambhava.

Indossando vesti color

zafferano e il cappello di

un ācarya, portava una

coppa-teschio nella mano

sinistra e, per tutta la

danza, la sua mano destra

era nel mudrā

dell'insegnamento. Anche

questa danza era lenta e

aggraziata: sollevava una

gamba tesa, si girava, poi

abbassava lentamente la

gamba, sollevava l'altra

gamba e così via. La danza è

chiamata "Yon-tan-gyi

rba-rlabs gYo-ba 'i "stang-stabs",

"Movimento delle onde

ondeggianti delle qualità

del Buddha", qui a indicare

le qualità di conoscenza e

saggezza contenute nei suoi

insegnamenti, poiché Padmasambhava è

essenzialmente l'aspetto di

Guru Padma come maestro di

Dharma che fondò il

monastero di bSam-yas e,

quindi, il Buddhismo in

Tibet. Con i cembali ancora

in funzione, i monaci

recitarono le sue lodi:

"Colui che ha pienamente

perfezionato tutte le

qualità del Buddha;

Lodo la forma di

Padmasambhava"

Torna all'inizio |

The next dance ought to have been that of Blo-ldan mChog-sred,

who is associated with the perfection of the intellectual

capacity. In accordance with the usual iconography, he wore

royal garments and held a damaru in his right hand and a vase of

red flowers in his left. The dance he would normally have

performed is called, "rMongs-pa'i mun-pa sel-ba'i stangs-stabs",

"Movement of clearing away the darkness of delusion" as he did

not dance, the monks simply recited his praise:

"The One who is undeluded regarding everything to be under-stood,

I praise the form of Blo-ldan mChog-sredl" |

|

La successiva avrebbe

dovuto essere

la

danza

di

Blo-ldan mChog-sred,

associato alla perfezione

delle capacità

intellettuali. Secondo

l'iconografia consueta,

indossava abiti regali e

teneva un damaru nella mano

destra e un vaso di fiori

rossi nella sinistra. La

danza che normalmente

eseguiva si chiama "rMongs-pa'i

mun-pa sel-ba'i stangs-stabs",

"Movimento per dissipare

l'oscurità dell'illusione".

Poiché non danzava, i monaci

si limitavano a recitare le

sue lodi:

"Colui che non è illuso

riguardo a tutto ciò che

deve essere compreso,

lodo la forma di Blo-ldan

mChog-sredl

|

Padma rGyal-po - "Lotus King" then performed the slow

and Majestic dance of "Khams gsum dbang-sdud-kyi stangs-stabs" ,

"Movement of bringing the three worlds under (his) power".

Dressed in the costume of a king with a mirror in his left hand,

the most striking feature of this dance is that he held up and

played a damaru in his right hand. Associated with the story of

Guru Padma as the Prince of O-rgyan, the wider significance of

this aspect is of the Guru as a king of the Dharma, controlling

the phenomenal world. The monks chanted the appropriate praise:

"The One who has brought the three spheres of existence (of) the

three worlds under his power;

I praise the form of Padma rGyal-po'"

|

|

Padma rGyal-po - "Re del

Loto" eseguì poi la

lenta e maestosa danza di

"Khams gsum

dbang-sdud-kyi stangs-stabs",

"Movimento per portare i tre

mondi sotto il suo potere".

Vestito con l'abito di un re

con uno specchio

nella mano sinistra, la

caratteristica più

sorprendente di questa danza

è che teneva in alto e

suonava un damaru

nella mano destra. Associato

alla storia di Guru Padma

come Principe di O-rgyan,

il significato più ampio di

questo aspetto è quello del

Guru come re del Dharma,

che controlla il mondo

fenomenico. I monaci

intonarono la lode

appropriata:

"Colui che ha portato le tre

sfere dell'esistenza dei tre

mondi sotto il suo potere;

Lodo la forma di Padma

rGyal-po"

|

The dance of Nyi-ma 'Od-zer followed. Although slow, as the

dances of the previous peaceful aspects, it involved his

whirling around on one leg and many arm movements.

Golden coloured, dressed as a yogi, wearing a mock tiger skin wrap and

brandishing a khatvÄnga in his right hand, this aspect

represents the activity of subduing through the transmutation of

the three poisons.

In one of the stories of Guru Padma, when

some TÄ«rthikas attempted to poison him, he transformed the

poison in amrta and demonstrated this form to subdue the TÄ«rthikas.

His dance is called, "'Gro-ba 'dul-ba'i stangs-stabs", "Movement

of subduing (all) beings".

The praise to him was recited:

"The One who removes the darkness of delusion,

subduer of all beings,

I praise the form of Nyi-ma 'Od-zer¡" |

|

Seguì

la

danza di Nyi-ma 'Od-zer.

Sebbene lenta, come le danze

dei precedenti aspetti

pacifici, prevedeva il suo

volteggiare su una gamba

e molti movimenti delle

braccia. Di colore dorato,

vestito come uno yogi, con

una finta pelle di tigre e

un khatvānga nella

mano destra, questo aspetto

rappresenta l'attività di

sottomissione attraverso la

trasmutazione dei tre

veleni. In una delle storie

di Guru Padma, quando alcuni

Tīrthika tentarono di

avvelenarlo, trasformò il

veleno in amrta e

mostrò questa forma per

sottomettere i Tīrthika. La

sua danza è chiamata "'Gro-ba

'dul-ba'i stangs-stabs",

"Movimento di sottomissione

(di tutti) gli esseri".

La lode a lui dedicata fu

recitata: Seguì

la

danza di Nyi-ma 'Od-zer.

Sebbene lenta, come le danze

dei precedenti aspetti

pacifici, prevedeva il suo

volteggiare su una gamba

e molti movimenti delle

braccia. Di colore dorato,

vestito come uno yogi, con

una finta pelle di tigre e

un khatvānga nella

mano destra, questo aspetto

rappresenta l'attività di

sottomissione attraverso la

trasmutazione dei tre

veleni. In una delle storie

di Guru Padma, quando alcuni

Tīrthika tentarono di

avvelenarlo, trasformò il

veleno in amrta e

mostrò questa forma per

sottomettere i Tīrthika. La

sua danza è chiamata "'Gro-ba

'dul-ba'i stangs-stabs",

"Movimento di sottomissione

(di tutti) gli esseri".

La lode a lui dedicata fu

recitata:

"Colui che rimuove

l'oscurità dell'illusione,

sottomesso di tutti gli

esseri,

Lodo laforma di Nyi-ma

'Od-zerl"

|

Next, the dance of Å akya Seng-ge should have been performed,

but as in the case of Blo-ldan mChog-sred, the monks simply

recited his prjaise:

"The One who subdues the four MÄras which lead beings astray,

I praise the form of Å akya Seng-gel"

His usual dance is known as, "bDud-phung 'joms-pa'i stang-stabs"

, "Movement of overcoming the host of Mara", the activity which

is, of course, associated with the Buddha Šakyamunťs attaining

of Enlightenment, and in this case, Guru Padma's equal

demonstration of Buddhahood. He was appropriately dressed in

accordance with the Tibetan portrayal of Sakyamuni, with the one

addition of a rdo-rje in his right hand. |

|

Poi,

avrebbe dovuto essere

eseguita la

danza di akya Seng-ge, ma come

nel caso di Blo-ldan

mChog-sred, i monaci

recitarono semplicemente

la sua lode:

"Colui che sottomette i

quattro Māra che sviano gli

esseri, S

lodo la forma di akya

Seng-gel"

La sua

danza abituale è conosciuta

come "bDud-phung 'joms-pa'i

stang-stabs", "Movimento per

sconfiggere la schiera di

Mara", attività che è,

ovviamente, associata al

raggiungimento

dell'Illuminazione da parte

del Buddha akyamuni e, in

questo caso, all'uguale

dimostrazione della Buddhità

da parte di Guru Padma.

Era

vestito in modo appropriato,

secondo la raffigurazione

tibetana di Sakyamuni, con

l'aggiunta di un

rdo-rje nella mano

destra.

|

|

Finally, the two wrathful aspects danced. First, Seng-ge

sGra-sgrogs performed his dance called, "Srii gsum gYo-ba'i

stang-stabs" , "Movement of shaking up the three worlds". This

is associated with his overturning the world-view of five

hundred TÄ«rthikas with destructive means. With a wrathful blue

mask and apron embroidered with a wrathful face, covered with a

mock tiger skin wrap, his dance was complex, faster than the

peaceful dances, with whirling and hopping from one foot to the

other.

His praise was as follows:

"The One who subdues the destructive spirits, the TÄ«rthikas;

I praise the form of Seng-ge sGra-sgrogs'"

As he completed his dance, a monk offered him a kha-btags (silk

scarf).

Then, a layman, on behalf of the lay community, offered a

kha-btags to the central figure of the Guru, and a monk offered

one on behalf of the monastic community. The monk also offered a

kha-btags to rDo-rje Gro-lod as he rose to dance. The offering

of kha-btags is one of the most common Tibetan ritual forms: it

expresses respect and gratitude.

The dance of rDo-rje Gro-lod is called, "Dregs-pa rtsa

gcod-kyi stang-stabs", "Movement of eradicating the Arrogant

Ones". rDo-rje Gro-lod is a really wrathful form of the

Guru, manifested for the purpose of subduing negative forces and

transforming them into Dharma protectors.

He has a special significance for the Rewalsar monks, since he

is the monastery's yi-dam, and his practice is performed daily,

both in the temple's main assembly hall and in the mGon-khang

(the Protector' s shrine-room. With a maroon wrathful mask and

dressed in a rich brocade outfit, an upper yellow robe and a

mock tiger skin wrap, he wielded a rdo-rje and phur-pa and

danced majestically, like Seng-ge sGra-sgrogsf with more

movements than the peaceful dancers.

His praise was recited:

"The One who annihilates the obstacles and hostile forces of

pride ( dregs-pa );

I praise the form of rDo-rje Gro-lod''

rDo-rje Gro-lod returned to his seat, and the horns were played,

joining the cymbals which had accompanied the dances. Then, the

mkhan-po gave instruments playing, the Guru and his aspects rose

and followed the procession around the courtyard, the two

wrathful aspects again not remaining in file but dancing

whirling around as they circumambulated the courtyard. The monks

leading the procession halted beside the temple porchway while

the aspects walked in, with the dancing Seng-ge sGra-sgrogs and

rDo-rje Gro-lod following. After some final music, the

procession of monks followed them into the temple, and the

mkhan-po gave some further teaching. |

|

Infine, i due aspetti irati danzarono. Per primo, Seng-ge sGra-sgrogs eseguì la sua danza chiamata "Srii gsum gYo-ba'i stang-stabs", "Movimento di scuotimento dei tre mondi". Questa è associata al suo rovesciamento della visione del mondo di cinquecento Tīrthika con mezzi distruttivi.

|

|

|

Con una maschera blu irata e un grembiule ricamato con un volto

irato, coperto da una finta pelle di tigre, la sua danza era

complessa, più veloce delle danze pacifiche, con rotazioni e

saltelli da un piede all'altro.

La sua lode era la seguente:

"Colui che sottomette gli spiriti distruttivi, i Tīrthika;

lodo la forma di Seng-ge sGra-sgrogs'"

Al termine della sua danza, un monaco gli offrì una kha-btags (sciarpa di seta)..

Poi, un laico, a nome della comunità laica, offrì un kha-btags alla figura centrale del Guru, e un monaco ne offrì uno a nome della comunità monastica. Il monaco offrì anche una kha-btags a rDo-rje Gro-lod mentre questi si alzava per danzare. L'offerta del kha-btags è una delle forme rituali tibetane più comuni: esprime rispetto e gratitudine.

La danza di rDo-rje Gro-lod è chiamata "Dregs-pa rtsa gcod-kyi stang-stabs", "Movimento per sradicare gli Arroganti". rDo-rje Gro-lod è una forma irata del Guru, manifestata allo scopo di sottomettere le forze negative e trasformarle in protettori del Dharma. Ha un significato speciale per i monaci Rewalsar, poiché è lo yi-dam del monastero e la sua pratica viene eseguita quotidianamente, sia nella sala principale delle assemblee del tempio che nel mGon-khang (sala sacrario del Protettore). Con una maschera adirata color marrone e vestito con un ricco abito di broccato, una tunica gialla superiore e una finta pelle di tigre, brandiva un rdo-rje e un phur-pa e danzava maestosamente, come Seng-ge sGra-sgrog con movimenti più veloci dei danzatori pacifici.

La sua lode veniva recitata:

"Colui che annienta gli ostacoli e le forze ostili

dell'orgoglio (dregs-pa);

Lodo la forma di rDo-rje Gro-lod''

rDo-rje Gro-lod tornò al suo posto e i corni furono suonati, unendosi ai cimbali che avevano accompagnato le danze. Poi, il mkhan-po diede gli strumenti, il Guru e i suoi Gli aspetti si alzarono e seguirono la processione intorno al cortile, con i due aspetti irati che ancora una volta non rimasero in fila, ma danzarono volteggiando mentre percorrevano il cortile. I monaci che guidavano la processione si fermarono accanto al portico del tempio mentre gli aspetti entravano, seguiti dai danzanti Seng-ge sGra-sgrogs e rDo-rje Gro-lod. Dopo un po' di musica finale, la processione dei monaci li seguì nel tempio e il mkhan-po impartì ulteriori insegnamenti.

Torna

all'inizio

|

|

|

|

THE GURU NÃTSHAN BRGYAD CHAMS:

THE SPECTATOR'S VIEWPOINT

Whether in practice, the dances constitute a "liberation through

seeing" for the spectators is not an easy question to answer,

but discussions on the significance of the dances with some of

those who had watched, provided a consistent picture of the way

the Tibetans view the dances.

The most immediate response on being asked their reasons for

watching the 'chams is that it is, "byin-rlabs chen-po "great

adhisthãna", quite different from entertainment such as

cinema, since it has a very power-ful and beneficial effect on

the mind. The idea of great byin-rlabs here is not simply that

the presence of the Guru arises briefly, during the 'chams, but

that the mental impression created by seeing him is so great

that it remains imprinted on one's mind. The significance of this is

that when one dies, there is a good likelihood that having once

seen him, one will be able to recognise his forms again, and

thus to be reborn in Zangs mdog dpal ri. Most informants

stressed that the "seeing" is not simply a passive process; as

each of the aspects danced, they would think, "This is Padma 'Byung-gnas

himself"; "This is Padmasambhava himself", and so on.

They either said that they would then do a supplication to each

aspect or that they would develop the aspiration to see them

again in Zangs mdog dpal ri.

One nun added that such an

aspiration is particularly powerful if coupled with regret at

one's previous negative actions, so that one thinks, "May my

negative actions not lead me to the hell realms; may they be

purified and may I gain birth in Zangs mdog dpal ri". A married

female practitioner emphasised that although the 'chams is very

powerful, it will not necessarily help if after observing it,

one continues life as though it has no relevance. It is

important to remind oneself of the presence of the Guru every

day, to do supplication and create the aspiration to realise

Buddhahood. |

|

IL GURU NÍTSHAN BRGYAD CHAM E IL PUNTO DI VISTA DELLO SPETTATORE

Se in pratica le danze costituiscano una "liberazione attraverso la visione" per gli spettatori non è una domanda facile a cui rispondere, ma le discussioni sul significato delle danze con alcuni di coloro che avevano assistito hanno fornito un quadro coerente del modo in cui i tibetani le vedono.

La risposta più immediata alla domanda sul perché assistessero alle 'cham è che si tratta di "byin-rlabs chen-po", "grande adhisthāna", molto diverso dall'intrattenimento come il cinema, poiché ha un effetto molto potente e benefico sulla mente. L'idea di grandi byin-rlabs qui non è semplicemente che la presenza del Guru si manifesti brevemente, durante i 'cham, ma che l'impressione mentale creata dal vederlo sia così forte da

rimanere impressa nella mente. Il significato di ciò è che quando si muore, c'è una buona probabilità che, dopo averlo visto una volta, si possa riconoscere di nuovo le sue forme e quindi rinascere in Zangs mdog dpal ri. La maggior parte degli informatori ha sottolineato che il "vedere" non è semplicemente un processo passivo; mentre ciascuno degli aspetti danzava, pensavano: "Questo è Padma 'Byung-gnas in persona"; "Questo è Padmasambhava in persona", e così via.

Entrambi hanno detto che avrebbero poi rivolto una supplica a ciascun aspetto o che avrebbero sviluppato l'aspirazione di rivederli in Zangs mdog dpal ri.

Una monaca ha aggiunto che tale aspirazione è particolarmente potente se unita al rammarico per le proprie azioni negative precedenti, tanto da pensare: "Che le mie azioni negative non mi conducano nei regni infernali; che possano essere purificate e che io possa rinascere in Zangs mdog dpal ri". Una praticante sposata ha sottolineato che, sebbene il 'cham sia molto potente, non sarà necessariamente d'aiuto se, dopo averlo osservato, si continua a vivere come se non avesse alcuna rilevanza. È importante ricordare a se stessi la presenza del Guru ogni giorno, pregare e coltivare l'aspirazione a realizzare la Buddhità.

Torna all'inizio

|

|

The mkhan-po said that as one spectates, one should perform the

Generation stage (bskyed-rim) meditation of dag-snang, "pure

appearances". This means that everything which arises is "pure"

or "empty" (Skt. sünya; Tib. stong-pa) in its nature, but

spontaneously appears as the display of the mandala. One should

not "grasp" the manifestations of the Guru as though they were

substantial, but should see them as being radiant andempty (gsal-stong).

Perfection of this meditation constitutes, "Liberation through

seeing". Most informants did not mention such a meditation that

could be spontaneously liberating, although one monk with years

of meditation experience, spoke in one breath of making

supplication, and doing the "radiant and empty" meditation. Faith or devotion, and

emptiness meditation are both integrated in most Vajrayana

practices.

The mkhan-po assumed that the practitioner would have

devotion to the Guru, while the other informants' comments were

made in the context of Tibetan Buddhist assumptions concerning

the nature of Zangs mdog dpal ri and its inhabitants, as

insubstantial, empty, clear and luminous. The difference is that

they emphasised the "gradual" approach to the Path. |

|

Il mkhan-po affermava che, osservando, si dovrebbe eseguire la meditazione dello stadio di Generazione (bskyed-rim) di dag-snang, "apparenze pure". Ciò significa che tutto ciò che sorge è "puro" o "vuoto" (skt. sünya; tib. stong-pa) nella sua natura, ma appare spontaneamente come manifestazione del mandala. Non si dovrebbero "afferrare" le manifestazioni del Guru come se fossero sostanziali, ma vederle come radiose e vuote (gsal-stong). La perfezione di questa meditazione costituisce la "Liberazione attraverso la visione". La maggior parte degli informatori non ha menzionato una meditazione che potesse essere spontaneamente liberatoria, sebbene un monaco con anni di esperienza di meditazione abbia parlato senza mezzi termini di supplica e meditazione "radiosa e vuota". La fede o devozione e la meditazione sulla vacuità sono entrambe integrate nella maggior parte delle pratiche Vajrayana.

Il mkhan-po dava per scontato che il praticante avrebbe avuto devozione per il Guru, mentre i commenti degli altri informatori erano espressi nel contesto dei presupposti del buddhismo tibetano riguardanti la natura di Zangs mdog dpal ri e dei suoi abitanti, come inconsistenti, vuoti, chiari e luminosi. La differenza è che enfatizzavano l'approccio "graduale" al Sentiero.

|

|

They recognised the aspects as manifestations of the Buddha-mind,

yet, feeling far from Realisation, the glimpse served as an

inspiration to aspire to a later rebirth in ZaÅgs mdog dpal ri.

On the other hand, the mkhan-po was concentrating on the

meditation of realising all appearances as they arise, to be

Zangs mdog dpal ri. Yet in practice, it would not be likely for

such a meditation to be instantaneously perfected, and it would

not conflict with practices which emphasise the relative level.

Clearly, each spectator will view the 'chams from the

perspective of their own level of practice, as well as that of

their own unique individual experience. In general, Tibetans are

aware of the Guru's presence as they watch, and feeling devotion

as a result, they aspire to be born in his Buddha-field.

Although some 'chams may be primarily oriented to bringing

about worldly benefits,33 such as auspicious circumstances or

the reinforcement of the lifeforce etc., this does not seem to

apply to the Guru mTshan brgyad 'chams. Its performance at

Rewalsar could be said to constitute an important component of

the reciprocity between monks and lay patrons, especially since it is performed at a time when the

lay villagers supporting the monastery are able to attend, and

the occasion is also used for their committee's annual business

meeting, when they discuss the monastery's financial and

practical needs.

However, in this instance, as in the case of much Dharma

teaching which lamas impart to their followers, the benefit

which the monks provide for the lay people is not equated with

worldly goals. |

|

Riconoscevano gli aspetti come manifestazioni della mente di Buddha, eppure, sentendosi lontani dalla Realizzazione, quella visione serviva da ispirazione per aspirare a una rinascita successiva in Zangs mdog dpal ri. D'altra parte, il mkhan-po si concentrava sulla meditazione di realizzare tutte le apparenze nel loro sorgere, per essere Zangs mdog dpal ri. Tuttavia, nella pratica, non sarebbe stato probabile che tale meditazione si perfezionasse istantaneamente, e non sarebbe entrata in conflitto con pratiche che enfatizzano il livello relativo. Chiaramente, ogni spettatore vedrà i 'cham dalla prospettiva del proprio livello di pratica, così come da quella della propria esperienza individuale unica. In generale, i tibetani sono consapevoli della presenza del Guru mentre lo osservano e, provando devozione di conseguenza, aspirano a rinascere nel suo campo di Buddha.

Sebbene alcuni 'cham possano essere principalmente orientati a portare benefici mondani, come circostanze propizie o il rafforzamento della forza vitale, ecc., questo non sembra applicarsi al 'cham del Guru mTshan brgyad. Si potrebbe dire che la sua esecuzione a Rewalsar costituisca una componente importante della reciprocità tra monaci e patroni laici , soprattutto perché viene eseguita in un momento in cui i laici del villaggio che sostengono il monastero possono partecipare, e l'occasione è anche utilizzata per la riunione annuale del loro comitato, durante la quale si discutono le esigenze finanziarie e pratiche del monastero .

Tuttavia, in questo caso, come nel caso di molti insegnamenti del Dharma che i lama impartiscono ai loro seguaci, il beneficio che i monaci forniscono ai laici non è equiparato a obiettivi mondani. |

Torna all'inizio

Torna all'inizio

[ Redazionale AnM ] [ Mappa Ladakh Zanskar ] [ Itinerario ] [ Acclimatazione ] [ Meteo ] [ Passeggiate ] [ Cham ] [ Guida ] [ Ambiente ] [ Zanskar ] [ Bardan Gompa ] [ Ladakh in Libreria ] [ Gruppi in Ladakh ]

|